Quck answer

Snakes are fascinating creatures that have evolved unique adaptations for survival. Their long, flexible bodies allow them to move quickly and quietly through their environment, and their specialized jaws and teeth enable them to swallow prey whole. Snakes also use heat-sensing organs to detect prey and predators, and some species are able to glide through the air. Despite their reputation as dangerous predators, many snakes are harmless and play important roles in their ecosystems as both predators and prey. Understanding the biology and behavior of snakes can help us appreciate and protect these fascinating animals.

Wild Animals

Also known as Water Moccasin, the Cottonmouth snake is a reptile that has been a part of world mythology and popular culture for centuries. While some tales depict them as dangerous, others show them with respect and admiration.

With over 130 million years of existence, snakes have evolved to be highly versatile vertebrates that can climb, swim and even fly without any limbs. They have a global presence and can be deadly, making them the stuff of myths and legends.

In this article, we’ll uncover some of the mysteries surrounding snakes. We’ll learn about their movement, hunting techniques, eating habits, reproduction and also discover some of the fascinating species that exist.

Understanding the Basics of Snakes

There are 2,700 known species of snakes, and they all share similar characteristics:

- They have slender, limbless bodies.

- They are carnivores.

- They are cold-blooded (ectothermic) which means their body temperature depends on their surroundings.

Snakes and lizards belong to the order Squamata, and while they look alike, they have some distinct differences. Snakes’ organs are arranged linearly due to their long shape, but they are otherwise similar to other vertebrates, including humans. The brain and sensory organs are in the head, and snakes have senses similar to humans but with some unique modifications.

Snakes have unique senses of hearing, sight, and smell. They do not have outer ears, but sound waves hit their skin and are transferred to their inner ear. Snakes do not see colors, but their eyes have rods and cones that provide low-light and clear vision. Some species also have pit organs that detect heat sources. Snakes breathe in airborne smells and use their tongue to transfer odor particles to their olfactory chamber. The digestive tract of a snake is stretchable and can digest prey larger than its diameter. Snakes do not have a diaphragm and circulate air by narrowing and widening their rib cage. They also experience apnea after each breathing cycle. Two-headed snakes are like conjoined twins and rarely survive in the wild due to duplicated senses and potential for self-cannibalism.

Learn More

Structure and Development of Snakes

Sidewinder snake (also known as “horned rattlesnake”)

Snakes can measure from a mere 4 inches (10 cm) to over 30 feet (9 meters) in length. They have hundreds of tiny vertebrae and ribs that span their bodies and connect through a complex system of muscles, which allows them to have unparalleled flexibility (refer to the Getting Around section). An extremely stretchy skin is attached to the muscles and covered with scales made of keratin, the same substance found in human fingernails. The scales are produced by the epidermis, which is the outer layer of skin. As snakes grow, the number and pattern of their scales remain the same, though the scales themselves are shed multiple times throughout their lives.

In contrast to humans who shed worn-out skin regularly in small pieces, snakes shed all of their scales and outer skin in one go through a process known as molting. When the skin and scales start to wear down due to age or injury, the epidermis begins to create new cells to separate the old skin from the developing inner layer. The new cells liquefy, causing the outer layer to soften. When the outer layer is ready to shed, the snake rubs the edges of its mouth against a hard surface like a rock until the outer layer starts to fold back around its head. It continues scraping and crawling until it is entirely free of the dead skin. The molting process, which takes around 14 days, is repeated after a few days to a few months.

Like humans, snakes grow rapidly until they reach maturity, which can take between one to nine years. However, their growth, though much slower after maturity, never stops. This is known as indeterminate growth. Depending on the species, snakes can live from four to over 25 years.

Snakes’ Movement Techniques

The key to snakes’ agility is their hundreds of vertebrae and ribs, which is closely linked to their locomotion: ventral scales. These specialized rectangular scales line the underside of a snake, corresponding directly with the number of ribs. The bottom edges of the ventral scales act like the tread on a tire, gripping the surface and propelling the snake forward.

Snakes have four fundamental methods of movement:

Snakes use different types of movement to get around, depending on their environment. The most common method is serpentine or undulatory locomotion, where the snake contracts its muscles from the neck and thrusts its body from side to side, creating curves. This motion propels the snake forward in water by pushing against the water, while on land, the snake uses its scales to push against resistance points like rocks or branches to move forward. In environments with few resistance points, snakes use sidewinding, creating an S-shape with only two points of contact with the ground to move laterally. Caterpillar or rectilinear locomotion is a slower method that has smaller curves that move up and down, lifting the tops of each curve above the ground. For climbing, snakes use the concertina technique, extending its head and front body along a vertical surface and gripping with its ventral scales while bunching up the middle of its body to find new places to grip.

Although snakes cannot fly, there are five species of “flying” snakes found in Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia. They swing themselves into the air from high branches and glide using S-shaped motions to keep themselves in the air, but they cannot fly upward. The anaconda, the heaviest snake in existence, is also an excellent swimmer. Found in the jungles of South America, the anaconda lives near slow-moving rivers and swamps and uses serpentine locomotion to move faster in water than on land. With its eyes and nostrils on the top of its head, the anaconda can see prey and breathe while hiding its body beneath the surface. It can hold its breath for up to 10 minutes and gives birth and copulates in the water. To feed, the anaconda uses constriction to suffocate and drown its prey.

Snake Digestion: A Look at What Snakes Eat

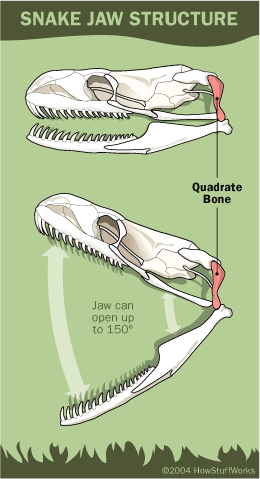

Despite the different hunting methods used by various snake species, their eating habits are fundamentally the same. Their highly flexible jaws allow them to consume prey that is much larger than their own size, by swallowing them whole. Unlike humans, whose upper jaw is fused to the skull, a snake’s upper jaw is attached to its braincase by muscles, tendons and ligaments, allowing it to move in different directions. The lower jaw is connected to the upper jaw by a double-jointed hinge, which enables the lower jaw to dislocate, allowing the mouth to open up to 150 degrees. The bones that make up the sides of the jaws are not fused together at the front, unlike human chins, and are instead connected by muscles, which allows the sides to separate and move independently of one another. This flexibility comes in handy when the snake encounters prey larger than its head, as its head can stretch to accommodate it.

When a snake is ready to eat, it opens its mouth wide and starts to “walk” its lower jaw over the prey, while its backward-curving teeth grab onto the animal. One side of the jaw pulls in while the other side moves forward for the next bite. The snake covers the prey with saliva and eventually pulls it into the esophagus. From there, it uses its muscles to crush and push the food deeper into the digestive tract, where it is broken down for nutrients.

Eating a live animal can be challenging even with all of these advantages. Some snakes have developed the ability to inject venom into prey to kill or subdue the animal before eating it. Some venom can even jump-start the digestion process. Snakes with this effective tool must have an equally effective way of getting the poison into an animal’s system: fangs.

Venomous snakes have two sharp teeth at the front or back of their upper jaw that are hollowed out to allow the venom to pass through. When a snake strikes and inserts these teeth into its prey, the venom is squeezed from a gland under each eye into the venom duct, where it passes more glands that release compounds that make the venom more potent, and out through the venom canal in the fangs.

In non-venomous, constrictor snakes, the teeth are stationary. In snakes with long (grooved) fangs, the teeth fold backward into the mouth when not in use, otherwise, the snake would puncture the bottom of its own mouth.

Although venomous snake species make up only one-fifth of all snakes, each has its own unique venom. The following are the three most important types of toxins found in snake venom:

The effects of snake venom can be categorized into three types: neurotoxins, cardiotoxins, and hemotoxins. Neurotoxins seize up the nerve centers, which can cause breathing to stop. Meanwhile, cardiotoxins deteriorate the muscles of the heart, causing it to stop beating. Lastly, hemotoxins make blood vessels rupture, leading to widespread internal bleeding. Some venom may also include agglutinins, which make the blood clot, or anticoagulants, which make the blood thin. Most snakes use a combination of these compounds for a deadly effect. Some snakes use constriction to squeeze the life out of their prey. The boa constrictor, for example, suffocates and kills its prey before eating it whole. It uses its prehensile tail to hang from trees and drop down on prey. When it comes to snake sex, a female releases a special scent to attract a sexually mature male. The male courts the female by bumping his chin on the back of her head and crawling over her. When she is willing, he wraps his tail around hers, and they mate. Female snakes reproduce about once or twice a year, and they use a variety of methods for giving birth, such as laying eggs or giving birth to live young.

Additional Information

Related Articles

- How Alligators Operate

- How Animal Disguise Functions

- How Bats Operate

- How Cicadas Work

- How Evolution Occurs

- How Mosquitoes Operate

- How Sharks Function

- How Spiders Operate

- How Venus Flytraps Work

- How Whales Operate

More Useful Links

- Singapore Zoological Docents

- Nashville Zoo: Anacondas

- Enchanted Learning: Boa Constrictors

- National Geographic: New Snake Footage Unveils Mystery of Flying Serpents

- National Geographic: Life Is Confusing For Two-Headed Snakes

- Encyclopedia.com: Snake

- Encyclopedia.com: Venom

References

- Singapore Zoological Docents

- Nashville Zoo: Anacondas

- Enchanted Learning: Boa Constrictors

- National Geographic: New Snake Footage Unveils Mystery of Flying Serpents

- National Geographic: Life Is Confusing For Two-Headed Snakes

- Encyclopedia.com: Snake

- Encyclopedia.com: Venom

FAQ

1. What are snakes?

Snakes are elongated, legless, carnivorous reptiles that belong to the suborder Serpentes. They have a long, cylindrical body covered with scales, a forked tongue, and no limbs. There are over 3,000 species of snakes, and they come in a wide range of colors, sizes, and patterns.

2. How do snakes move?

Snakes move by using their muscles to push and pull against surfaces. They use their belly scales to grip the ground and create friction, which propels them forward. Some snakes can also swim by using a similar motion, but with their body flattened and their scales used to paddle through the water.

3. How do snakes eat?

Snakes eat their prey whole, using their jaws to stretch open their mouth and swallow the animal. Some snakes have specialized teeth that are used to inject venom into their prey, while others simply constrict their prey to death. Once the prey is swallowed, the snake’s digestive system goes to work breaking down the food.

4. How do snakes breathe?

Snakes breathe through their lungs, just like humans. However, their lungs are elongated and run almost the entire length of their body. Snakes can also breathe through their skin, but this is a less efficient method of respiration.

5. How do snakes reproduce?

Snakes reproduce sexually, with males depositing sperm into the female’s body during copulation. The female then lays eggs or gives birth to live young, depending on the species. Some snakes are oviparous, meaning they lay eggs, while others are viviparous, meaning they give birth to live young.

6. How do snakes protect themselves?

Snakes have a variety of methods for protecting themselves, including camouflage, venomous bites, and warning displays. Some snakes will hiss, rattle their tails, or puff up to make themselves look bigger and more intimidating. Others simply blend in with their environment, making them difficult to spot.

7. How do snakes sense their environment?

Snakes have a highly developed sense of smell, which they use to locate prey and navigate their environment. They also have specialized pits on their faces that allow them to sense heat, which helps them locate warm-blooded prey. Some snakes also have excellent vision and can see in the dark.

8. How do snakes shed their skin?

Snakes shed their skin as they grow, typically in one piece. The old skin is pushed off by the growth of new skin underneath, and the snake then crawls out of the old skin. This process is called ecdysis and can occur several times a year, depending on the species and individual.

9. How do snakes hibernate?

Some snakes hibernate during the winter months to conserve energy and survive the cold temperatures. They will typically find a sheltered location, such as a burrow or rock crevice, and enter a state of torpor. During this time, their metabolism slows down and they do not eat or move much until the warmer weather returns.

Leave a Reply